The Sanctuary Movement (1980-1991)

"And you are to love those who are foreigners" — Deuteronomy 10:19 (NIV)

'Obedience to God requires this of us all'

Empower

Growth

Spanning the 1980s, the Sanctuary Movement was a direct challenge by more than 500 American interfaith religious congregations to U.S. government policy denying Central American refugees asylum. While directly providing refuge to displaced migrants, the movement protested and raised awareness about the United States' funding and training of military dictatorships and militias that fomented the violence and instability that forced Central Americans north.

This website is a public history project that seeks to make the story of the Sanctuary Movement accessible and understandable while contextualizing it within the U.S. involvement in Central America and U.S. immigration policy, as well as the traditions on which Sanctuary activists drew.

Besides creating changes in U.S. immigration policy, galvanizing the first local and state governments to declare their jurisdictions as "sanctuary," and energizing similar religious efforts around the globe, the Sanctuary Movement's legacy continues to fuel work by the faithful to "love the stranger" as the Hebrew scriptures command.

The image above depicts the arrest of Father Luis Olivares in downtown Los Angeles on November 22, 1989. Olivares and others were blocking the federal building entrance as part of a protest against U.S. policy in El Salvador. As pastor at Our Lady Queen of Angels Church, also known as La Placita, Olivares officially declared La Placita to be a sanctuary congregation in 1985. To learn more about Olivares and La Placita's role in the Sanctuary Movement, check out Mario T. Garcías's book Father Luis Olivares. The image is part of the Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library at University of California, Los Angeles.1

1. Mario T. García, Father Luis Olivares, A Biography: Faith Politics and the Origins of the Sanctuary Movement in Los Angeles (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

Gloriosa victoria by Diego Rivera is a tempera-on-canvas painting created in 1954 and depicts General Castillo Armas making a pact with the U.S. government. Depicted are U.S. ambassador to Guatemala John Peurifoy, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, CIA Director Allen Dulles, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower on the face of the bomb. In the background is a United Fruit Company ship and Archbishop Mariano Rossell y Arellano officiating a mass over the massacred bodies of the workers. By TortugaHalo - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=111495920

Historical Context

Central American conflict & U.S. involvement

There were fewer than 50,000 Central American immigrants in the United States in 1960. In the two decades that followed, that number would multiply by seven. By 1990, the number would top one million. Natural disaster, civil war, and political violence were driving most of these migrants north from countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. Their arrival in the United States was complicated by U.S. involvement with repressive regimes in their home countries and Cold War policies.

Click HERE to read more.

The Cold War

& U.S. Immigration Policy

It was against a Cold War backdrop that the United States orchestrated events and became involved in Central American civil wars. The Cold War influenced how refugees from war torn southern neighbors were received when they arrived in the United States. The Reagan administration saw the Central American civil wars as "theaters in the Cold War" and its policy toward refugees reflected that by labeling them as "economic migrants" to avoid implication that U.S.-supported regimes were guilty of human rights violations. Click HERE to read more.

A 1975 internal CIA memo described the agency's role in the overthrow of Guatemalan

President Jacobo Arbenz. FOIA Electronic Reading Room, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)

"I've got 21 Salvadorans in my house—can we bring some to your church?"

Declaring Sanctuary

In March 1982, Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson,

Arizona publicly declared that it would offer sanctuary

to Central American refugees in defiance of federal laws.

Pastor John Fife and the congregation had been offering

assistance to Central American immigrants crossing the border

in the form of legal aid, food assistance, and medical care

for two years when Quaker activist Jim Corbett approached

Fife and said that in order to be faithful, they had break the law.

"He said to me, 'John, I think we have to start smuggling refugees across the border so they're not captured under these conditions because once they're captured by border patrols, then they're deported back to El Salvador and possible death squads,'" Fife recounted during a 2022 Presbyterian Historical Society program about the Sanctuary Movement. Before telling Fife that it was time for the faithful to break the law, Corbett had told Fife that none of the El Salvador migrants were getting asylum.1

Fife remembered Corbett telling him to consider the Abolition Movement's Underground Railroad. "As we read history," Corbett said, "they got it right. They were faithful ... Now look at the failure, almost total failure, of the church in Europe to protect Jews who were fleeing the Holocaust and others fleeing Nazi Germany ... That's one of the most tragic failures of church faith in history ... I don't think we can allow that to happen on our border in our time can we?"2

A short time later, Corbett's wife, Pat, told Fife, "I've got 21 Salvadorans in my house—can we bring some to your church?"3

From there, the question went to Southside Presbyterian Church's session (a governing body of elders in the local church), and the session brought it to a congregational meeting. For five hours in a January 1982 meeting, the congregation wrestled with the decision of whether to break the law to help those fleeing political violence in Central America. Seventy-nine of the congregants voted in favor of sanctuary. One of the two voting against sanctuary immediately reported the church's decision to the FBI.4

The church went public with their declaration. On January 23, 1982, Fife wrote federal attorneys and the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and on January 24, before eight TV news crews, he read the church's sanctuary declaration.5

In his letter to U.S. Attorney General William French on March 23, 1982, Fife wrote:

We are writing to inform you that Southside United Presbyterian Church will publicly violate the Immigtarion and National Act, Section 274(A) ...

We take this action because we believe the current policy and practice to the U.S. government with regard to Central American refugees is illegal and immoral. We believe our government is in violation of the 1980 Refugee Act and international laws by continuing to arrest, detain, and forcibly return refugees to terror, persecution, and murder in El Salvador and Guatemala.

We believe that justice and mercy require that people of conscience actively assert our God-given right to aid anyone fleeing from persecution and murder. The current administration of the United States law prohibits us from sheltering these refugees from Central America. Therefore we believe that administration of the law is immoral and illegal.

We beg of you, in the name of God, to do justice and love mercy in the administration of your office. We ask that 'extended voluntary departure' be granted to refugees from Central America and that current deportation proceedings against these victims be stopped.

Until such time, we will not cease to extend the sanctuary of the church to undocumented people from Central America. Obedience to God requires this of us all.5,6

In the next year, more than 1,600 Salvadorans would find sanctuary at Southside before being moved to safe houses in other parts of the United States.7

On March 24, 1982, the second anniversary of Archbishop Óscar Romero's assassination by a right-wing death squad in El Salvador, five Berkeley, California, congregations joined Southside in coordinated press conferences to announce publicly that they too would be offering sanctuary to Central American refugees in defiance of the law. The five Berkley congregations were: University Lutheran, St. John's Presbyterian, St. Joseph the Worker, St. Mark's Episcopal, and Trinity Methodist.8

The East Bay Sanctuary Covenant

The Bay Area has become a place of uncertain refuge for men, women and children who are fleeing for their lives from the vicious and devastating conflict in Central America. Many of these refugees have chosen to leave their country only after witnessing the murder of close friends and relatives.

The United Nations has declared these people legitimate refugees of war; by every moral and legal standard, they ought to be received as such by the government of the United States. The 1951 United Nations Convention and the 1967 Protocol Agreements on refugees—both signed by the U.S.—established the rights of refugees not to be sent back to their countries of origin. Thus far, however, our government has been unwilling to meet it’s [sic] obligations under these agreements. The refugees among us are consequently threatened with the prospect of deportation back to El Salvador and Guatemala, where they face the likelihood of severe reprisals, perhaps including death.

This is not the first time religious people have been called to bear witness to our faith in providing sanctuary to refugees branded “illegal” in their flight from persecution. The slaves also fled north in our own country and the Jews who fled Nazi Germany are but two examples from recent history. We believe the religious community is now being called again to provide sanctuary to the refugees among us.

Therefore, we join in covenant to provide sanctuary—support, protection, and advocacy—to the El Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees who request safe haven out of fear and persecution upon return to their homeland. We do this out of concern for the welfare of these refugees, regardless of their official immigrant status. We acknowledge that legal consequences may result from out action. We enter this covenant as an act of religious commitment.

1. "PHS Live: Sanctuary and Accompaniment," Presbyterian Historical Society, April 19, 2022, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7zVt0TMBXY.

2. "PHS Live."

3. Kyle Paoletta, "What the Birth of the Sanctuary Movement Teaches Us Today," April 10, 2025, The Nation, https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/how-the-sanctuary-movement-actually-began/.

4. "PHS Live."

5. Gary MacEoin, Sanctuary: A Resource Guide for Understanding and Participating in the Central American Refugees Struggle, ed. Gary MacEoin (San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers, 1985), 21-22.

6. Kristina M. Campbell, "Operation Sojourner: The Government Infiltration of the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980s and its Legacy in the Modern Central American Refugee Crisis," University of St. Thomas Law Journal 13, no. 3 (2017): 478.

7. "PHS Live."

8. Kat Jerman, "Berkley's Sanctuary Movement," November 25, 2016, San Francisco Digital History Archive, https://www.foundsf.org/Berkeley%27s_Sanctuary_Movement.

Traditions that Rooted the Sanctuary Movement

Ancient Origins

Examples of sanctuary can be found in civilizations around the world since ancient times. In Hebrew scriptures and in Athens, cities of refuge were designated for those fleeing vengeance.1 Romulus, legendary founder of Rome, designated

Capitoline Hill as a place of sanctuary.2 In Uncertain Refuge: Sanctuary in the Literature of Medieval England, author Elizabeth Allen writes: "The idea of divine protection in a sacred space did not owe its inception to Christianity; idea of sacred protection existed in cultures as geographically varied as Hawaii, Morocco, and Japan and as ancient as biblical cities of refuge and Greek Temples."3

1. Ann Deslandes, "Sanctuary Cities Are as Old as The Bible," March 22, 2017, JSTOR Daily,

https://daily.jstor.org/sanctuary-cities-as-old-as-bible/.

2. Alexander G. Thein, "Asylum: Map Entry 154," Digital Augustan Rome, Accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.digitalaugustanrome.org/records/asylum/.

3. Elizabeth Allen, Uncertain Refuge: Sanctuary in the Literature of Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 1-3.

Scriptural Basis

"Say to the Israelites: Appoint the cities of refuge, of which I spoke to you through Moses." -Joshua 20:2

"The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the native-born among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God." - Leviticus 19:34

"Then the king will say to those at his right hand, 'Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world, for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.' ... 'Truly I tell you, just you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me.'"

-Matthew 34-40

Scripture translations are from

the New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition

Medieval Law

In 12th Century England, royal law allowed those accused of crimes, owing debts, or fleeing cruel enslavers to seek sanctuary in churches, churchyards, cathedrals and monasteries. At the end of forty days, the sanctuary-seeker had to leave their refuge and stand trial, confess their crimes and take their punishment, or give up all they owned and go into exile for the rest of their lives—unless some kind of agreement could be reached during the forty days of refuge.

The forty days gave time for tempers to cool, for conversations to take place, and for

evidence to be considered. This law had evolved out of English common law, which varied depending upon the time and place,

before the 1100s. By the late Middle Ages, exile was less common and permanent sanctuary within sacred spaces

was common.1,2

1. Elizabeth Allen, Uncertain Refuge: Sanctuary in the Literature of Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 1-3.

2. J.C. Cox, The Sanctuaries and Sanctuary Seekers of Medieval England (London: George Allen & Sons, 1911), 4.

Underground Railroad

Those within the Sanctuary Movement likened their work to the Underground Railroad through which abolitionists—often acting on principles of faith—had illegally helped people escaping slavery to places of safety before the U.S. Civil War. Like the abolitionists, Sanctuary Movement workers broke the law to shelter refugees in churches and homes until safety—oftentimes precarious safety—could be achieved. Even before the first congregation declared sanctuary, an underground railroad that would move refugees to safe houses was developing. According to Robert Tomsho in The American Sanctuary Movement, this underground railroad would eventually stretch from San Salvador and Guatemala City to Seattle, Chicago, and Boston.1

1. Robert Tomsho, The American Sanctuary Movement (Austin: Texas Monthly Books, 1987), 20.

Draft Resisters

Some historians root the Sanctuary Movement as beginning during the Vietnam War in which U.S. involvement spanned nearly two decades, ending in 1973. As congregations answered spiritual calls to resist the war, several churches announced they would provide sanctuary to those who were resisting the military draft. In one example, nine draft resisters, who would come to be known as the "Buffalo Nine," took sanctuary in the Elmwood Avenue Unitarian Universalist Church in Buffalo, New York. Federal agents, and Buffalo Police stormed the church, arresting resisters and their supporters. One of the nine arrested was sentenced to three years in prison but fled to Sweden where he was given asylum.1

1. Mark Sommer, "Bruce Beyer, 70, prominent Buffalo Nine anti-war activist," Vietnam Full Disclosure, Veterans for Peace, April 16, 2019, https://www.vietnamfulldisclosure.org/ bruce-beyer-70-prominent-buffalo-nine-anti-war-activist/.

Liberation Theology

Liberation theology is a theology that prioritizes the poor and oppressed, and this way of understanding sacred teachings had a great influence on Sanctuary Movement workers. Born out of Latin American Catholicism, liberation theology can be found in some Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and other faith expressions. Liberation theology emphasizes social justice and liberation from oppressive structures. Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez authored A Theology of Liberation, published in 1971, and is regarded as the father of liberation theology. Gutiérrez wrote that theology was worthless unless it was "in active participation to liberate humankind from everything that dehumanizes it and prevents it from living according to the will of the Father."1

1. Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1971), 174.

A group of people gather in the Federal Building plaza to protest US aid to El Salvador’s military government during the Salvadoran Civil War, Chicago, February 7, 1982.

ST-30002672-0027, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Bob Black | Chicago History Museum, https://www.chicagohistory.org/sanctuary-in-chicago/

'No trespassing, for the ground upon which you walk is holy'

An international underground railroad

This is the time and we are the people to reinvoke the ancient law of sanctuary, to say to the government, 'You shall go this far and no further.' This is the time and we are the people fleeing the blood vengeance of the powers that be in El Salvador. We provide a safe place and cry, 'Basta! Enough! the blood stops here at our doors.' This is the time to claim our sacred right to invoke the name of God in this place—to push back all the powers of violation and violence in the name of the Spirit to whom we owe our ultimate allegiance. At this historic moment we are the people to tell Caesar, 'No trespassing, for the ground upon which you walk is holy.

—Rev. David Chevrier, pastor, Wellington Avenue United Church of Christ, Chicago, 19821

After the first six congregations declared sanctuary in 1982, dozens more took similar actions and in less than a year, there were 45 churches and synagogues that had declared sanctuary and 600 additional congregations and groups that were endorsing and supporting the work. By 1984, 150 congregations had declared sanctuary and 18 national religions denominations had endorsed the movement. In 1985, the Central Conference on American Rabbis endorsed the movement and the number of congregations declaring sanctuary had grown to 250, and by 1987 nearly 400. Sanctuary workers in Mexico and the United States helped refugees illegally cross the border and then transported them to nearby congregations who sheltered them until they could be moved further north to other churches, synagogues, or homes that were part of the movement. Sanctuary congregations committed to meeting refugees' needs from housing and education to health care and legal services.2

The Chicago Religious Task Force had been formed after the murders of three U.S. Maryknoll nuns and a lay missionary by Salvadoran National Guard members in El Salvador in 1980. "The slogan, Haz patria, mata un cura ('Be a patriot, kill a priest') became a battle cry for Salvadoran right-wing extremists who believed that anyone who opposed the military regime was a communist, including religious figures," writes Stephanie M. Huezo in Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective.3

The task force on Central America, made up of both religious and activists groups, took on the role of coordinating the underground railroad of the international Sanctuary Movement. The task force's work included coordinating transportation and placement for those coming into sanctuary as well as printing and distributing literature, "including a 'nuts and bolts' manual for Sanctuary organizers with detailed instructions on every phase of the process and how to use it as a political tool."4

A 2009 article in Latin American Perspectives describes the first refugees to be welcomed to Pico Rivera United Methodist Church in Los Angeles. Juan and Rosa Jiménez were educators who fled El Salvador when Juan "discovered he was being investigated by the Salvadoran government for allowing peasants to use printing equipment for antigovernment pamphlets. Several teachers they knew had been killed. A classroom [at the church] was converted into living quarters, and the congregation provided food, clothing, English classes, and a small weekly allowance."4

Because the movement was decentralized, it is impossible to say how many refugees were assisted by Sanctuary congregations during the 1980s. Some estimates place the number as high as 3,000.5

1. Ignatius Bau, This Ground is Holy: Church Sanctuary and Central American Refugees (New York: Paulist Press, 1985), 9.

2. Norma Stoltz Chinchilla, Norma Hamilton, and James Loucky, "The Sanctuary Movement and Central American Activism in Los Angeles," Latin American Perspectives 36, no. 6 (November 2009), 6-7.

3. Stephanie M. Huezo, "The Murdered Churchwomen in El Salvador," Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, December 2020, https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/murdered-churchwomen-el-salvador?language_content_entity=en.

4. Norma Stoltz Chinchilla, 6.

5. Norma Stoltz Chinchilla, 12.

6. Ignatius Bau, 12.

Carl and Kathy Hersh, reporters who had covered the wars in Central America, turned their eye to recording the growing Sanctuary Movement in the United States in their 1983 documentary The New Underground Railroad. The documentary includes recorded discussions within congregations as they grapple with whether to become part of the movement.

Hersh, Carl, dir. The New Underground Railroad. 1983. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/204907964.

Sanctuary Workers arrested, indicted, tried

FBI and INS Launch Operation Sojourner

Operation Sojourner was a 10-month investigation of the Sanctuary Movement that involved infiltration and secret surveillance of congregations and included undercover agents attending, participating in, and recording worship services and church meetings. Click HERE to read more.

Indictment and Trials

of Activists

Sixteen Sanctuary Movement workers, including priests, nuns, and ministers, were indicted on federal charges of conspiracy to illegally transport and harbor Central American refugees. Ultimately, six were convicted . Click HERE to read New York Times coverage of the trials.

Listen as Mary Ann Lundy talks with David Staniunas about her experiences as a Sanctuary activist during a 2022 conversation for the Presbyterian Historical Society. Lundy was placed on home arrest after refusing to testify against other Sanctuary workers and held in contempt of court. Lundy said: "I choose not to testify on the basis of my First Amendment right to freedom of religion and I invoke my privilege as a Presbyterian elder not to speak against my community of faith." Lundy died on March 11, 2025. Read her obituary here.

Mary Ann Lundy, interview by David Staniunas, Presbyterian Historical Society, March 16, 2022.

'If I am guilty of anything, then I am guilty of living out the Gospel'

21st Century Legacy of the Sanctuary Movement

"If I am guilty of anything, than I am guilty of living out the Gospel ... The only conspiracy we ere involved in here is a conspiracy of love."

—Sister Darlene Nicgorski, convicted of alien smuggling, conspiracy, and harboring for her work in the Sanctuary Movement1

With Sanctuary Movement workers jailed, tried, and sentenced, those who had been providing illegal aid to Central American refugees vowed to continue, and new congregations and organizations joined the movement even as government pressure increased. The end of the 1980s movement really came about as political violence lessened in Central America in the early 1990s, decreasing the need for sanctuary. Additionally, the movement won the ABC Settlement, the Immigration Act of 1990 passed, and other policies were changed and created to support Central American refugees.

However, some say the movement never ended.

As early as 2006, organizing efforts calling themselves "The New Sanctuary Movement" emerged in response to increasingly harsh detention and deportation policies with the creation of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection in 2003.

In May 2007, the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations endorsed the New Sanctuary Movement, becoming the first national denomination to do so.2 As of 2018, the Sanctuary Movement website sanctuarynotdeportation.org, reported more than 1,000 houses of worship involved in the movement with twelve public sanctuary cases in 2014, three in 2015, six in 2016, and 37 in 2017.3

In the wake of Donald Trump's 2016 election, T'ruah: The Rabbinic

Call for Human Rights began to connect Jewish communities to the

New Sanctuary Movement and reports that more than seventy

synagogues are members of the Mikdash Sanctuary Network.

"This isn't about politics, or the First Amendent," Rabbi Mona Alfi said

in May 2017 when her Sacramento congregation became a sanctuary

synagogue. "We felt that based on our own history as immigrants, as

refugees, as survivors of the Holocaust, it would be sinful for us to

remain silent. We understand what the risks are, but the risk of not

acting is much more perilous."4

What the future holds for Sanctuary Movement work is precarious.

At the start of Trump's second term in 2025, his administration announced it would allow federal agents to enter schools, hospitals, and churches to make arrests of undocumented people. Since 2011, agents had been restricted from carrying out immigration enforcement in such "sensitive locations" and were required to get advance approval before any actions in such places.5

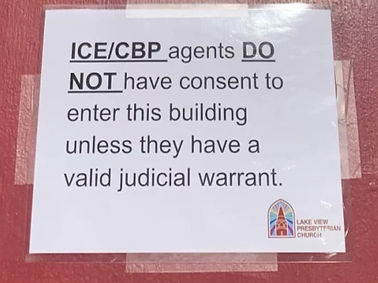

Pastors report posting signs on church doors informing agents they do not have consent to enter places or worship.

1. Kristina M. Campbell, "Operation Sojourner: The Government Infiltration of the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980s and its Legacy in the Modern Central American Refugee Crisis," University of St. Thomas Law Journal 13, no. 3 (2017): 489.

2. "New Sanctuary Movement," Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.uua.org/files/documents/washingtonoffice/sanctuary_issuebrief.pdf.

3. "Sanctuary in the Age of Trump," Sanctuary Movement, January 2018, https://sanctuarynotdeportation.org/uploads/7/6/9/1/76912017/sanctuary_in_the_age_of_trump_january_2018.pdf.

4. "Mikdash: A Jewish Guide to the New Sanctuary Movement," T'ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights, Accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.truah.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/mikdash-p-10-11-history-of-sanctuary.pdf.

5. Rebecca Santana, "Migrants can now be arrested at churches and schools after Trump administration throws out policies," PBS News, January 22, 2025, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/migrants-can-now-be-arrested-at-churches-and-schools-after-trump-administration-throws-out-policies.

What impact did the Sanctuary Movement have?

Raising Moral Concerns and Shifting the

Public Conversation

The Sanctuary Movement challenged the public conversation about Central American refugees and their treatment by the U.S. by raising moral concerns . The rooting of those moral concerns in faith traditions shared by millions of Americans shifted understanding and perspectives.

American Baptist

Churches v. Thornburgh

(ABC Settlement)

A lawsuit filed by more than 70 religious and human rights organizations in 1985 led to the ABC Settlement in 1991, which gave 300,000 denied Salvadoran and Guatemalan asylum seekers protection from deportation, work authorization, and new asylum interviews. Click HERE to read more.

Influencing the Immigration Act of 1990

The influence of the Sanctuary Movement was felt in the Immigration Act of 1990, which included provisions for Central American refugees. This revision of the 1965 Immigration Act, created Temporary Protected Status so that asylum seekers could remain in the U.S. until conditions in their home country improved.

Temporary ProtectedStatus (TPS)

Temporary Protected Status is often seen as the most lasting change to come from the Sanctuary Movement. Part of the Immigration Act of 1990, TPS allows refugees from designated countries to receive protection from deportation, authorization to work, and other benefits until conditions improve so that they may return to their home countries. TPS was initially created for Salvadoran refugees, but was expanded to other countries.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals

TPS was the model for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). DACA was established by President Barack Obama in 2012 as a policy to protect certain undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children. Those covered under DACA received protection from deportation

and work authorization.1

Susan Bibler Coutin, "Sanctuary Then and Now," Society for Cultural Anthropology, October 19, 2021, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/sanctuary-then-and-now.

Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act

Congress enacted the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act in 1997 after a backlog in processed asylum applications from Guatemalans and Salvadorans prevented these two groups

of refugees from receiving legal status.

More than 80,000 Salvadorans and Guatemalans who had been in the U.S. since 1990 and who benefited under the

ABC Settlement became legal

permanent residents.

Sanctuary Cities & States

While Los Angeles passed a policy in 1979 that local police were not to concern themselves with residents' immigration status, the sanctuary city movement really started to grow with public outrage at the treatment of Central American refugees and the prosecutions of Sanctuary Movement workers. In 1985, Berkley City Council declared the entire city as a sanctuary for undocumented refugees, and San Francisco declared itself a "City of Refuge" for Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees. The declarations of local governments to provide sanctuary to undocumented immigrants continues to grow. In 2017, California was the first state to declare itself as "Sanctuary." Today it is joined by at least nine other states and more than 200 cities in declaring sanctuary within its boundaries.1

1. "The Sanctuary Movement," California Migration Museum," Accessed February 26, 2025, https://www.calmigration.org/learn-chapter/sanctuary-movement.

Global Faith-Based Sanctuary Projects

The U.S. Sanctuary Movement influenced similar faith-based

projects around the world that continue. European religious sanctuary projects are inspired by the U.S. movement, but also draw on the Medieval history of sanctuary to inform their work.1 Germany, Australia, Israel, Canada, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Trinidad, Iceland, Sweden, Norway, and Finland are among countries that have or have had active religious sanctuary projects since the 1980s.2

1. Katharyne Mitchell and Key MacFarlane, "The sanctuary network: transnational church activism and refugee protection in Europe" in Handbook on Critical Geographies of Migration, ed. Katharyne MItchell, Reece Jones, and Jennifer L. Fluri (Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019), 415.

2. Derek Burnett, "Is a Global Sanctuary Movement an Answer to the Refugee Crisis?," Sojourners, May 6, 2018, https://sojo.net/articles/global-sanctuary-movement-answer-refugee-crisis.

Learn more about the Sanctuary Movement

Sanctuary: On the Border Between Church and State (above) is a 10-episode podcast series that explores the politics of immigration, faith as radical hospitality, and the borders between church and state. Distributed by Axis Mundi Media, its creators and narrators are Dr. Lloyd Barba of Amherst College and Dr. Sergio Gonzalez of Marquette University.

"The Sanctuary Movement" is a website created by Amherst College Department of Religion with resources on the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s-1990s, the New Sanctuary Movement, and other forms of immigrant rights activism. Click here to visit the website:

Bibliography

Allen, Elizabeth. Uncertain Refuge: Sanctuary in the Literature of Medieval England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

“American Baptist Churches (ABC) v. Thornburgh.” A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States. Library of Congress, Accessed April 30, 2025. https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/abc-v-thornburgh.

“American Baptist Churches v. Thornburgh.” Center for Constitutional Rights. October 9, 2007. https://ccrjustice.org/home/what-we-do/our-cases/american-baptist-churches-v-thornburgh.

“American Baptist Churches v. Thornburg (ABC) Settlement Agreement.” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. September 3, 2009. https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-and-asylum/asylum/american-baptist-churches-v-thornburgh-abc-settlement-agreement.

Applebome, Peter. “Sanctuary trial leaves a political aftertaste.” The New York Times, July 6, 1986. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1986/07/06/142586.html?pageNumber=91

Austin, Charles. “More churches join in offering sanctuary for Latin refugees.” The New York Times, September 21, 1983. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1983/09/21/178974.html?pageNumber=18.

Barba, Lloyd and Sergio Gonzalez. “Spies in the Pews.” Sanctuary: On the Border Between Church and State. October 17, 2024. Podcast, 1:01:14. https://open.spotify.com/episode/4WStnxTR1BBjTjioZqr3Nv?si=srszUi3mSg2cUls_PV2Gtw.

Bau, Ignatius. This Ground is Holy: Church Sanctuary and Central American Refugees. New York: Paulist Press, 1985.

Bishop, Katherine. “Sanctuary groups sue to halt trials.” The New York Times, May 8, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/05/08/us/sanctuary-groups-sue-to-halt-trials.html?searchResultPosition=31.

Brockett, Charles. Political Movements and Violence in Central America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Burnett, Derek. "Is a Global Sanctuary Movement an Answer to the Refugee Crisis?" Sojourners. May 6, 2018. https://sojo.net/articles/global-sanctuary-movement-answer-refugee-crisis.

Cain, Seth. “El Salvador 1979-92.” Study of Internal Conflict (SOIC) Case Studies, Study Sequence No. 9, April 2024. Strategic Studies Institute at the U.S. Army War College. https://media.defense.gov/2025/Apr/07/2003683788/-1/-1/0/20250407_ELSALVADOR_1979-92_FINAL.PDF.

Campbell, Kristina M. "Operation Sojourner: The Government Infiltration of the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980s and its Legacy in the Modern Central American Refugee Crisis." University of St. Thomas Law Journal 13, no. 3 (2017): 474-507.

“Charges against two nuns in sanctuary case dropped,” The New York Times, February 13, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/02/13/024276.html?pageNumber=20.

Chinchilla, Norma Stoltz, Norma Hamilton, and James Loucky. "The Sanctuary Movement and Central American Activism in Los Angeles." Latin American Perspectives 36, no. 6 (November 2009): (101-126).

Corbett, Jim. “Pamphlet 270: The Sanctuary Church.” Wallingford, PA: Pendle Hill Publications, 1986.

Coutin, Susan Bibler. "Sanctuary Then and Now." Society for Cultural Anthropology. October 19, 2021. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/sanctuary-then-and-now.

Cox, J.C. The Sanctuaries and Sanctuary Seekers of Medieval England. London: George Allen & Sons, 1911.

Deslandes, Ann. "Sanctuary Cities Are as Old as The Bible," March 22, 2017. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/sanctuary-cities-as-old-as-bible/.

Gammage, Sarah. “El Salvador: Despite End to Civil War, Emigration Continues” Migration Policy Institute, July 26, 2007. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/el-salvador-despite-end-civil-war-emigration-continues.

García, Mario T. Father Luis Olivares, A Biography: Faith Politics and the Origins of the Sanctuary Movement in Los Angeles. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Getchell, Michelle Denise. “Revisiting the 1954 Coup in Guatemala: The Soviet Union, the United National, and the ‘Hemispheric Solidarity.” Journal of Cold War Studies 17, no. 2 (2015). Accessed April 19, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1162/JCWS_a_00549.

Golden, Renny and Michael McConnel. Sanctuary: The New Underground Railroad. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1986.

Gonzalez, Juan. Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America. New York: Penguin Books, 2000.

Gutiérrez, Gustavo. A Theology of Liberation. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1971.

Gzesh, Susan. “Central Americans and Asylum Policy in the Reagan Era.” Migration Information Source. The Online Journal of the Immigration Policy Institute. April 1, 2006. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-americans-and-asylum-policy-reagan-era.

Hersh, Carl, dir. The New Underground Railroad. 1983. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/204907964.

Holding, Katherine. “Operation Sojourner: The Prosecution of the Practice of Faith.” The Sanctuary Movement. Amherst College Department of Religion. December 2020. https://sanctuary.wordpress.amherst.edu/sanctuary-columns/kholding/.

Huezo, Stephanie M. "The Murdered Churchwomen in El Salvador." Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective. December 2020. https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/murdered-churchwomen-el-salvador?language_content_entity=en.

Jerman, Kat. "Berkley's Sanctuary Movement." November 25, 2016. San Francisco Digital History Archive, https://www.foundsf.org/Berkeley%27s_Sanctuary_Movement.

King, Wayne. “Activists vow to continue aiding people fleeing Central America.” The New York Times, January 16, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/01/16/219515.html?pageNumber=1.

King, Wayne. “Church sanctuary worker gets 2-year term.” The New York Times, June 21, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/06/21/068401.html?pageNumber=12.

King, Wayne. “Church worker acquitted in alien case, buoying movement.” The New York Times, January 25, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/01/25/240414.html?pageNumber=10.

King, Wayne. “Informers are assailed in refugee-harboring case.” The New York Times, August 4, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/04/us/informers-are-assailed-in-refugee-harboring-case.html.

King, Wayne. “Two go on trial in Houston for illegally helping aliens.” The New York Times, February 19, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/02/19/038108.html?pageNumber=10.

King, Wayne. “U.S. judge bars religious issue in aliens case.” The New York Times, July 26, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/07/26/147712.html?pageNumber=8.

King, Wayne. “U.S. seeking a curb on testimony citing religion in sanctuary case.” The New York Times, January 27, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/01/27/244541.html?pageNumber=13.

Lundy, Mary Ann. By David Staniunas. Presbyterian Historical Society. March 16, 2022. https://digital.history.pcusa.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A284911

MacEoin, Gary. Sanctuary: A Resource Guide for Understanding and Participating in the Central American Refugees Struggle. Edited by Gary MacEoin. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers, 1985.

Mary Ann Lundy Papers, RG 522. Presbyterian Historical Society. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. https://pcusa.org/historical-society/collections/research-tools/guides-archival-collections/rg-522.

“Memorandum Prepared in the Central Intelligence Agency: Subject-CIA’s Role in the Overthrow of Arbenz.” May 12, 1975. Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1952-54Guat/d287.

"Mikdash: A Jewish Guide to the New Sanctuary Movement." T'ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://www.truah.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/mikdash-p-10-11-history-of-sanctuary.pdf.

Mitchell, Katharyne and Key MacFarlane. "The sanctuary network: transnational church activism and refugee protection in Europe." In Handbook on Critical Geographies of Migration. Edited by Katharyne MItchell, Reece Jones, and Jennifer L. Fluri. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019.

"New Sanctuary Movement." Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://www.uua.org/files/documents/washingtonoffice/sanctuary_issuebrief.pdf.

Oster, Ryan. “Guatemalan Civil War 1960-96.” Study of Internal Conflict (SOIC) Case Studies, Study Sequence No. 36, March 2024. Strategic Studies Institute at the U.S. Army War College. http://media.defense.gov/2024/Mar/20/2003416572 /-1/-1/0/20240306_GUATEMALANCIVILWAR_1960-96.PDF.

Ovryn, Rachel. “Targeting the Sanctuary Movement.” CovertAction Information Bulletin no. 24 (1985): 12-15.

Paoletta, Kyle. "What the Birth of the Sanctuary Movement Teaches Us Today." April 10, 2025. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/how-the-sanctuary-movement-actually-began/.

"PHS Live: Sanctuary and Accompaniment." Presbyterian Historical Society. April 19, 2022. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7zVt0TMBXY.

“President Reagan gives CIA authority to establish Contras.” History.com. January 31, 2025. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/november-17/reagan-gives-cia-authority-to-establish-the-contras.

“Reagan Doctrine, 1985.” U.S. Department of State archive. https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/rd/17741.htm.

Reagan, Ronald. “Address to the Nation on the Situation in Nicaragua.” March 16, 1986. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/address-nation-situation-nicaragua

“Refugee Act of 1980.” National Archives Foundation. https://archivesfoundation.org/documents/refugee-act-1980/.

Reinhold, Robert. “Churches and U.S. Clash on Alien Sanctuary.” The New York Times, June 28, 1984. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1984/06/28/031948.html?pageNumber=1.

Ripley III, Charles G. “Crisis Prompts Record Emigration from Nicaragua, Surpassing Cold War Era.” Migration Policy Institute, March 7, 2023. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/record-emigration-nicaragua-crisis.

“Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992).” “‘Burning with a Deadly Heat’: NewsHour Coverage of the Hot Wars of the Cold War.” American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Accessed April 19, 2025. https://americanarchive.org/exhibits/newshour-cold-war/el-salvador.

"Sanctuary in the Age of Trump." Sanctuary Movement. January 2018. https://sanctuarynotdeportation.org/uploads/7/6/9/1/76912017/sanctuary_in_the_age_of_trump_january_2018.pdf.

“'Sanctuary' Worker Convicted in Alien Trial.” The New York Times, May 15, 1984. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1984/05/15/193237.html?pageNumber=14.

Santana, Rebecca. "Migrants can now be arrested at churches and schools after Trump administration throws out policies." PBS News. January 22, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/migrants-can-now-be-arrested-at-churches-and-schools-after-trump-administration-throws-out-policies.

“Six convicted, five cleared of plot to smuggle in aliens for sanctuary.” The New York Times, May 12, 1986. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1986/05/02/896486.html?pageNumber=19.

Smith, Christian. Resisting Reagan: The U.S. Central America Peace Movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Smith, James. “Guatemala: Economic Migrants Replace Political Refugees.” Migration Policy Institute, April 1, 2006. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/guatemala-economic-migrants-replace-political-refugees.

Sommer, Mark. "Bruce Beyer, 70, prominent Buffalo Nine anti-war activist." Vietnam Full Disclosure. Veterans for Peace. April 16, 2019. https://www.vietnamfulldisclosure.org/ bruce-beyer-70-prominent-buffalo-nine-anti-war-activist/.

Stoney, Sierra, and Jeanne Batalova. “Central American Immigrants in the United States.” Migration Policy Institute, March 18, 2013. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states-2011.

Takahashi, Maria Luiza. “Nicaragua (Contras) 1978-90.” Study of Internal Conflict (SOIC) Case Studies, Study Sequence No. 19, August 2024. Strategic Studies Institute at the U.S. Army War College. https://media.defense.gov/2024/Oct/02/2003557339/-1/-1/0/20241001_NICARAGUA%20(CONTRAS)_1978-90.PDF.

Thein, Alexander G. "Asylum: Map Entry 154." Digital Augustan Rome. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.digitalaugustanrome.org/records/asylum/.

“The Iran-Contra Affair.” American Experience, Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed April 19, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/reagan-iran/.

“The Sanctuary Movement.” California Migration Museum. Accessed February 26, 2025. https://www.calmigration.org/learn-chapter/sanctuary-movement.

Tomsho, Robert. The American Sanctuary Movement. Austin: Texas Monthly Books, 1987.

“Two who aided Salvadorans get jail sentences.” The New York Times, March 28, 1985. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/03/28/124060.html?pageNumber=20.

“United States v. Maria del Scorro Pardo de Aguilar (1985).” Center for Constitutional Rights, October 9, 2007. https://ccrjustice.org/home/what-we-do/our-cases/united-states-v-maria-del-scorro-pardo-de-aguilar-1985.

Volsky, George. “U.S. churches offer sanctuary to aliens facing deportation.” The New York Times, April 8, 1983. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1983/04/08/086234.html?pageNumber=1.